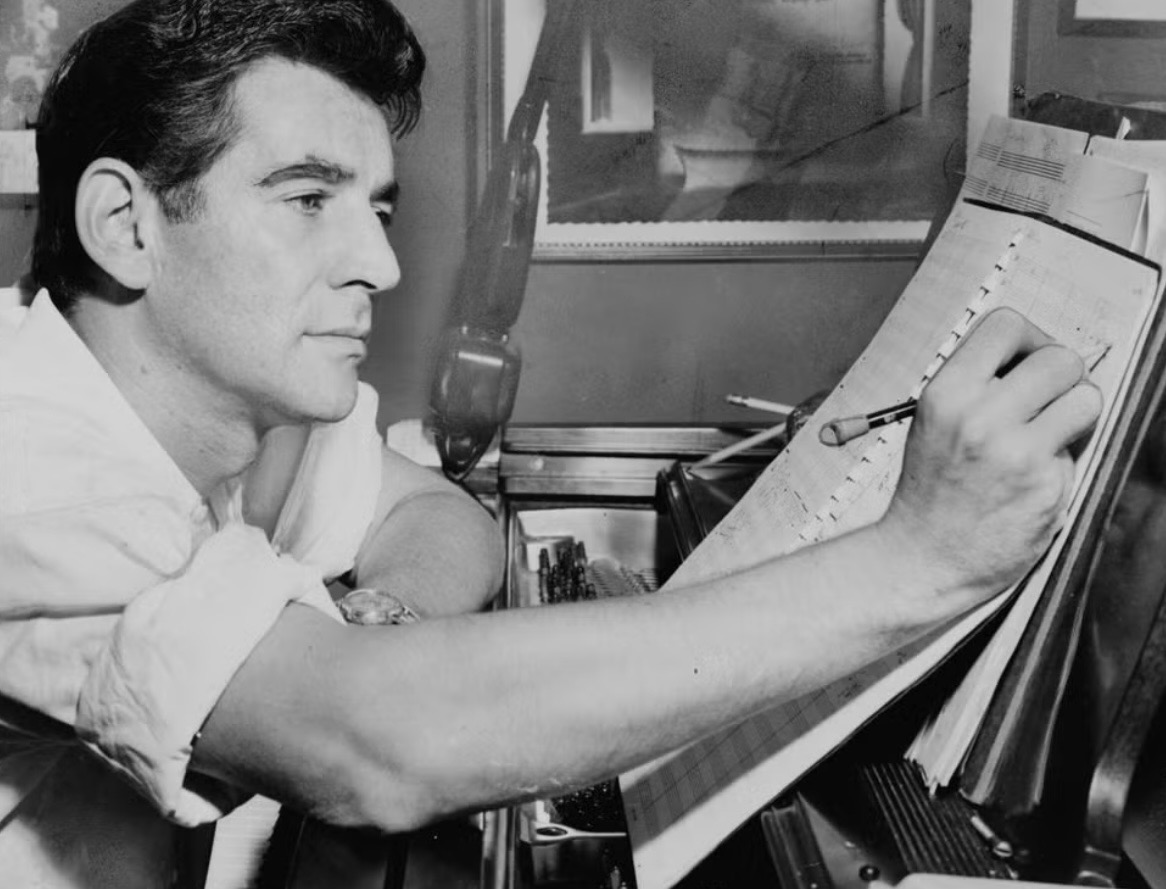

Leonard Bernstein remains one of the most influential figures in 20th-century music. A world-renowned conductor, composer, and educator, he transformed the New York Philharmonic, collaborated with the world’s elite orchestras, and brought classical music into living rooms across the globe through television. From the gritty urban rhythms of West Side Story to his profound symphonies and the avant-garde MASS, Bernstein’s creative reach was boundless. The following on new-york-trend.com a look at the life and career of a true American icon.

The Path to a Calling

Leonard Bernstein was born on August 25, 1918, in Lawrence, Massachusetts, to Jewish immigrants from Rivne (modern-day Ukraine). His father, Sam Bernstein, lived the quintessential immigrant story: starting with backbreaking labor on New York’s Lower East Side and working his way up to a successful business distributing beauty and barber supplies. To Sam, success meant financial stability and a practical trade; music, by contrast, seemed like a frivolous whim—hardly a foundation for a serious future. It was against this domestic resistance that young “Lenny” began to find his voice.

Music entered his life almost by accident. When he was ten, his Aunt Clara, in the midst of a divorce, left her large upright piano with the family. For Leonard, it was the discovery of an entire universe. He was hooked from the first touch, but his father refused to pay for lessons. Undeterred, Lenny began earning his own money, giving private lessons to younger children in the neighborhood. His talent soon became so undeniable that Sam Bernstein finally relented, eventually gifting his son a baby grand. From that moment on, music was no longer a forbidden dream.

Bernstein would later remark:

“Life without music is unthinkable. Life without music is academic. That is why my contact with music is a total embrace.”

During his time at Boston Latin School, Lenny met the woman who would become his first true mentor: Helen Coates. She didn’t just teach him piano; she remained his professional assistant for the rest of his life. However, the turning point came in 1937. At a Boston Symphony Orchestra concert, Bernstein saw conductor Dimitri Mitropoulos. The maestro’s magnetic style—conducting without a baton—left Leonard spellbound. A personal introduction and a week spent watching Mitropoulos rehearse convinced him once and for all to dedicate his life to the podium.

Following graduation, Bernstein headed to Harvard to study theory and composition, then moved on to the Curtis Institute to sharpen his conducting technique under the rigorous tutelage of Fritz Reiner. In 1940, at Tanglewood, he met Serge Koussevitzky. The legendary conductor became his mentor, cementing Bernstein’s belief that music is a profound spiritual and social force. By then, his path to the world’s great stages was set in stone.

The Night That Changed Everything

Despite an inspiring summer at Tanglewood, Leonard Bernstein soon found himself unemployed. His talent was undeniable and his passion bottomless, but the reality of the music industry was unforgiving. For a while, he scraped by transcribing music and taking odd jobs. It seemed as though luck had passed him by—until history took a sudden, dramatic turn.

World War II had thinned the ranks of American orchestras as many musicians were called to serve. When the New York Philharmonic needed an assistant conductor, Bernstein accepted an offer from Music Director Artur Rodziński, becoming the youngest person ever to hold the position. Just a few months later, fate handed him a moment that would go down in history.

On November 14, 1943, guest conductor Bruno Walter suddenly fell ill. With no time for a rehearsal and no room for doubt, Rodziński ordered the 25-year-old Bernstein to take the podium at Carnegie Hall. It was a leap into the unknown—and the opportunity of a lifetime.

Bernstein didn’t just manage; he triumphed. The orchestra, the audience, and radio listeners across the country witnessed the birth of a superstar. The next day, The New York Times ran the story on the front page, hailing it as a classic American success story. Overnight, Leonard Bernstein became a household name, conducting the Philharmonic eleven more times before the season ended.

From that point on, his career skyrocketed. He conducted in New York and toured throughout the U.S., Europe, and Israel, while simultaneously making his mark as a theatrical composer. In 1944, he teamed up with choreographer Jerome Robbins to create the ballet Fancy Free—the story of three sailors in wartime New York. It was such a hit that it quickly evolved into the Broadway musical On the Town. The show became a sensation, eventually landing on the silver screen starring Gene Kelly and Frank Sinatra.

By the 1950s, Bernstein had become a polymath of American culture. This era saw the debut of Trouble in Tahiti, Wonderful Town, Candide, and, finally, the work that would define his legacy forever. West Side Story was a bold reimagining of what a musical could be. By transplanting Shakespearean tragedy to the streets of New York and infusing it with jazz, Latin rhythms, and social grit, Bernstein created music that felt urgent, sharp, and brutally honest.

Leonard Bernstein had evolved from a young substitute conductor into the voice of New York, America, and an entire generation. He was the musician who proved that classical music could live in the “here and now,” speak the language of the streets, and still remain timeless.

A New Era for the New York Philharmonic

In 1957, Leonard Bernstein was appointed Music Director of the New York Philharmonic. Initially sharing the podium with his mentor, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Bernstein took full command of the orchestra just one year later. He became the first American-born conductor to lead the Philharmonic in its history. He remained Music Director until 1969 and later received the honorary title of Laureate Conductor, maintaining a deep bond with the orchestra through live performances and legendary studio recordings until the end of his life.

Under his leadership, music education broke free from the confines of the concert hall. In a bold move, Bernstein brought the Young People’s Concerts—a Saturday tradition—to national television on CBS. What began as an experiment became a global cultural phenomenon. Millions of viewers worldwide discovered classical music through Bernstein’s charisma, wit, and raw passion.

Between 1958 and 1972, he produced 53 televised concerts—a series critics still hail as the most influential music education program in TV history. The project earned multiple Emmy Awards, and the transcripts of his lectures were later published as books and audio recordings. One of them, Humor in Music, even won him a Grammy.

Bernstein also transformed the Philharmonic into a global powerhouse. In 1958, he led the orchestra’s first tour of Central and South America as a diplomatic mission sponsored by the U.S. State Department. The following year, the Philharmonic embarked on a massive tour of Europe and the Soviet Union. The climax was a performance of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony in the presence of the composer himself. When Shostakovich took to the stage to congratulate Bernstein, it became a defining moment for music as a universal language that transcends politics.

The 1960s were a decade of relentless innovation. Bernstein shattered traditions, introduced themed programming, and revived the works of long-ignored composers. Under his baton, the Philharmonic opened its doors to the city. In 1965, he launched free concerts in New York City parks, insisting that the orchestra belonged to every resident. He also championed social progress within the institution: during his tenure, the orchestra hired its first Black musician and its first female instrumentalist.

By refusing to play by the old rules, Bernstein turned the New York Philharmonic into a living, breathing organism of the modern era.

The Maestro-Mentor

In his later years, Leonard Bernstein realized that his true mission was no longer just conducting or composing, but passing the torch to the next generation. During the 1980s, he pioneered new educational spaces. In Los Angeles, alongside the Philharmonic’s leadership and USC faculty, he founded the Los Angeles Philharmonic Institute—a summer academy modeled after Tanglewood.

He famously told his students:

“To achieve great things, two things are needed: a plan, and not quite enough time.”

Across the Atlantic, Bernstein helped establish the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival Orchestra Academy in Europe. He didn’t just teach; he built a community. He toured Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union with his young protégés, demonstrating that music is a living, international language. His final major project was the Pacific Music Festival in Sapporo, founded in 1990 with Michael Tilson Thomas. That same year, he received the Praemium Imperiale, one of the world’s most prestigious arts awards. Without hesitation, he donated the $100,000 prize to launch the Bernstein Education Through the Arts (BETA) Fund.

After his passing, this initiative evolved into the Artful Learning program—an educational model that integrates the arts into general K-12 schooling and is still used in many American schools today.

In October 1990, Bernstein announced his retirement from conducting. Five days later, he passed away in his New York apartment from a heart attack brought on by cancer. He was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn next to his wife, with a pocket score of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony placed over his heart—the music he considered his personal confession.

Bernstein’s life was more than a triumph of the podium; it was proof that memory, responsibility, and dialogue can bridge the gap between high art and the hearts of millions.