This is not just a romantic comedy-drama, but a true visual poem about New York City. Director Woody Allen created a film that combines irony, self-deprecation, and sincere melancholy, intertwining a love story with the hero’s attempts to find himself in the big city. Read on new-york-trend.com for more about the creation of this masterpiece, which became a global cult classic.

A Love Symphony of the Big City

The film Manhattan begins as a gentle, almost musical ode to New York. Set to George Gershwin’s”Rhapsody in Blue,” the black-and-white shots of the city unfold—brilliant, contrasting, and eternally alive. For the main character, Isaac, a middle-aged writer, the city is part of his soul. He searches for meaning in life, creativity, and relationships, getting lost between irony and sincerity.

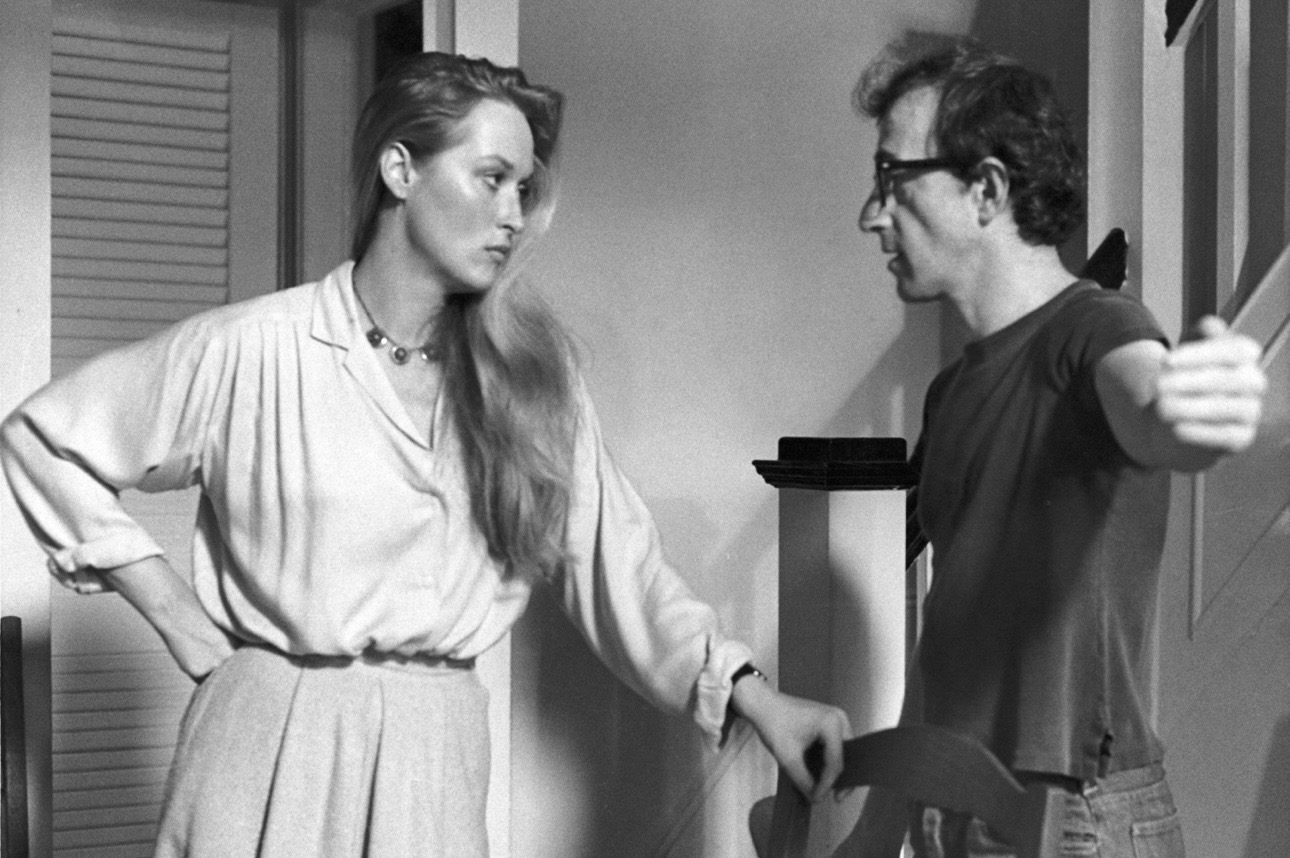

His personal life is a continuous state of uncertainty: his romance with 17-year-old Tracy seems safe but unstable, while his acquaintance with the intelligent, cynical Mary promises intellectual depth but brings pain. Add to this his ex-wife, who wrote a scandalous book about their marriage, and Isaac’s internal confusion becomes apparent.

The most iconic moment of the film is the scene under the Queensboro Bridge at dawn. This is more than just a beautiful shot—it’s a moment where love, the city, and loneliness merge into one. But romance in Manhattan always borders on disappointment. In the finale, Isaac, having lost everything, suddenly realizes what truly matters: the things that inspire him. And among the list of things that fill life with meaning, he remembers Tracy’s face. His attempt to win her back is too late, yet touching. Their brief farewell scene encapsulates the film’s main theme: the ability to believe, even when loss seems final.

Manhattan is not just a love story. It is a subtle, bittersweet reflection on growing up, the search for truth in an era of emotional confusion, and a sincere love letter to a city that never stops.

The Story Behind the Film

Woody Allen didn’t just make a film about New York—he declared his love for it using the language of cinema. The idea was born not from a screenplay, but from the music. Allen listened to the overtures of George Gershwin and felt: this sound is New York. It’s his New York. Thus, the idea arose to create a black-and-white romantic film breathing music and melancholy. He wrote the story with Marshall Brickman. The inspiration for the character of young Tracy came from Stacey Nelkin, Allen’s girlfriend at the time. Although other women, including Kristine Engelhardt, also believed the film was partially based on their stories, the director did not deny it. Tracy is more of a composite portrait, molded from several real people, youth, and nostalgia.

Allen wanted the city on screen to be a living entity, not just a backdrop. Together with cinematographer Gordon Willis, who was nicknamed the “Prince of Darkness” for his mastery of lighting, they decided the film must be black-and-white and shot in the Panavision 2.35:1 format. This format, according to Willis, allowed them to see the city expansively—as a symphony of lines, movement, and shadow. He called the visual style concept romantic realism: Manhattan is not as everyone sees it, but as they remember and love it.

The film’s most famous shot, featuring the characters on a bench near the Queensboro Bridge at dawn, was captured at five in the morning. The bench had to be brought in by the crew, and they negotiated with city services to keep the lights on until sunrise. When one of the string lights on the bridge went out during a take, Allen kept that shot—there was something genuine in its imperfection.

To capture the city’s play of light and shadow, Willis chose Kodak Double-X film—the fastest black-and-white stock of the time. It allowed him to play with contrast and create depth even in cramped interiors. For printing, they used Agfa positive film—a material with a higher silver content that yielded rich blacks and a sheen similar to old photographs.

Despite the film being about New York, many scenes were recreated outside the city. Some interiors were easier to build on a soundstage, where Willis could control the light down to the smallest detail. He aimed for the space to breathe reality even in artificial conditions—for the camera to “hear” the city even when it wasn’t visible. Although not all filming took place in Manhattan itself, the atmosphere is so authentic that the viewer can feel the smell of rain, the noise of the subway, and even the quiet breathing of dawn over the East River.

When the work was finished, Allen… wanted to destroy it. He felt the film was unsuccessful and even offered United Artists not to release it, promising to shoot his next film for free instead. Only later did he realize that he had created something more than just a love story.

New York in the Film

Allen filmed in real-life locations, and because of this, his New York appears not as a cinematic image, but as a living organism, full of contrasts and moods.

It is a city of paradoxes—beautiful and weary, glamorous and mundane, eternally young and old all at once.

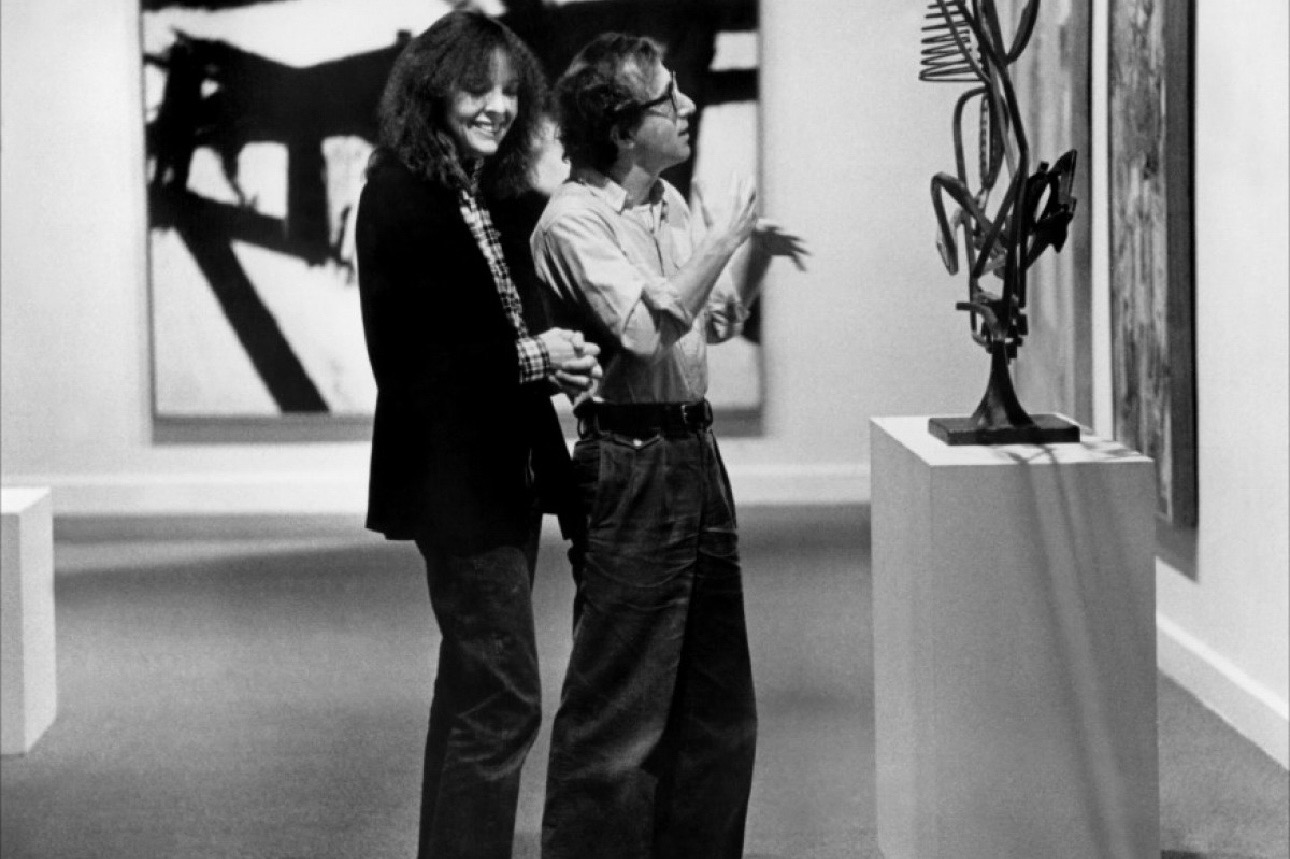

Allen’s characters meet and part in places where New York culture is born. They argue at the Museum of Modern Art, stroll amidst the spirals of the Guggenheim, take shelter from a thunderstorm at the Hayden Planetarium, and drink coffee at the legendary Elaine’s—a restaurant where the city’s bohemia gathered for decades. The restaurant is closed today, but in film history, it remains as a place where the humor, irony, and loneliness of the big city converged.

Allen consciously avoids tourist clichés. His camera captures unusual angles of New York—from John’s Pizza on Bleecker Street, where Tracy tells Isaac she’s leaving for London, to Zabar’s on West 80th, where the characters argue between aisles of delicacies.

Also featured are the Russian Tea Room near Carnegie Hall, Bloomingdale’s, where Mary meets with Yale, and even the former Rizzoli’s bookstore on West 57th, where Isaac discovers a new page in his life.

Each of these locations is like a chapter in a great book about New York. And while many of them have disappeared or changed, they are frozen on film in a perfect balance between reality and memory.

In the prologue, Allen shows shots that are now perceived as a visual ode to New York: the Staten Island Ferry, Lincoln Center, the Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum, and an old diner on Tenth Avenue—the very one that later appeared in Men in Black. These images are not just title cards but parts of a grand symphony where every instrument plays its own note. New York here is not a decoration—it is a mirror for the characters, their illusions and defeats, and their search for meaning amidst neon lights and old brick facades.

A Brilliant Premiere and Honorable Recognition

After its premiere in the spring of 1979, Manhattan became Woody Allen’s manifesto of love for the city that shaped him. When the film was released, its box office success was as surprising as its critical acclaim. It grossed nearly half a million dollars its opening weekend, and over three and a half million within two weeks. Eventually, the total box office take in the U.S. and Canada reached $39.9 million, making Manhattan the 17th most successful film of the year and the second most popular of Allen’s career (after Annie Hall). Adjusted for modern ticket prices, this amounts to over $140 million—an unprecedented result for a lyrical, almost intimate comedy.

But the film’s true value was defined not by numbers, but by the analytical reviews that followed the premiere.

Critics competed in their phrasing, trying to capture the essence of what Allen had achieved. Jack Kroll of Newsweek spoke of “the maturity of the author in every frame”—from the acting performances to the visual poetry. Roger Ebert, who initially gave the film three and a half stars, later declared Manhattan one of the greatest films of all time, including it in his “Great Movies” list.

Even those who saw certain flaws in the film admitted that Allen had created an incredibly accurate snapshot of urban life, where intellectual dialogues sound like jazz improvisations.

Manhattan subsequently became the standard for urban cinema, with its influence visible even in films far removed from the themes of love or New York. It was included in lists of the greatest films of all time by Empire, The New York Times, and Bravo, and in 2001, the U.S. Library of Congress officially recognized it as culturally, historically, and aesthetically significant.